The current generation of children and young people live in a fast-paced, hyper-digitalised world. The confluence of geopolitical, environmental, socioeconomic, technological, and cultural shifts facing the world’s 1.8 billion young people complicates how young people live, work, learn and interact and how organisations work with young people to ensure their wellbeing.

Additionally, by 2050, more than two-thirds of the world’s population will live in urban areas, in cities that are not ready to support them. From education to healthcare to employment, our city systems are failing young people and leaving them at risk of being left behind. There is an urgent need to transform urban environments, so they are inclusive and fit to support the health and wellbeing of young people.

In the face of these challenges, the pursuit of wellbeing often leads practitioners and organisations to focus on individual aspects of our lives: material needs, personal achievements, and physical health. However, the true nature of human existence is far more interconnected and complex than these isolated fragments.

Fondation Botnar recognises that wellbeing encompasses not only individual needs but also the web of connections we forge with others and the subjective perceptions that shape our experiences. This led us to delve into understanding wellbeing as relational, exploring its significance and foundations and how we can work with our partners to realise this in practice.

As part of the exploration, we developed the following animation reflecting on what wellbeing means to us.

What is wellbeing?

For us, wellbeing is defined as having autonomy over our lives, our experiences, and our emotions.

Our approach represents a shift from an often simplistic, siloed perspective that dominates discussions about human wellbeing. It is an approach that recognises that we exist within intricate networks of relationships, both with other people and the streets, cities, environments and systems around us.

In developing our relational approach to wellbeing we drew on the thinking of Sarah White and Shreya Jha of the Relational Wellbeing Collaborative and the University of Bath. They explain that a relational approach to wellbeing aims to facilitate a more holistic understanding of human experiences and interactions, acknowledging the dynamic interplay between material conditions, societal connections, and subjective perceptions that collectively define our quality of life. Wellbeing is constantly changing. A holistic approach focuses on the processes and drivers that create wellbeing and, therefore, such an approach – like wellbeing itself – is not static.

Why does a relational approach to wellbeing matter?

As we see it, wellbeing acknowledges the profound interconnectedness of human lives.

The story of Maria – a fictional character – illustrates the intersection of various elements in ensuring young people’s wellbeing.

Maria: an illustrative narrative

Imagine you’re Maria, a 19-year-old woman living in a fast-growing city in Colombia. You’ve finished high school and now help support your family through part-time work. These days, you’re thinking about your future and further education, but you’re not sure how your choices will affect your life.

Some days, you work at the local leisure centre to generate a small income for yourself and your family. Living with parents, grandparents, and siblings, there isn’t much space, but you rely on one another to ensure there is always enough to eat. Continuing your education in tourism and starting a travel business fills you with hope, but it isn’t easy to save, and there aren’t many opportunities for finding work in your field.

On weekends, you like to meet your friends and go to the local open-air food market to unwind. Despite ups and downs, their lives look much like yours, and you can relate to them — you feel safe and understood. When you have downtime, you use your mobile phone to learn English using an app where you receive a free subscription. Your friends encourage you to continue learning and open your tourism business.

Your city is growing and changing quickly. When you think about the future, you’re worried about where and how you fit into it and how the decisions you make now could impact the lives of those around you. You feel a mixture of hope and fear.

People’s lives don’t exist in one dimension but as a complex, interconnected web of needs and desires, relationships and social pressures. By reducing our focus to only one aspect at a time, we risk losing the bigger picture of wellbeing — and how one element can affect another.

Taking a relational approach to wellbeing means appreciating the full context of an individual’s unique lived experience, understanding and developing projects and programmes that consider those needs and address them at multiple levels.

A relational approach in practice

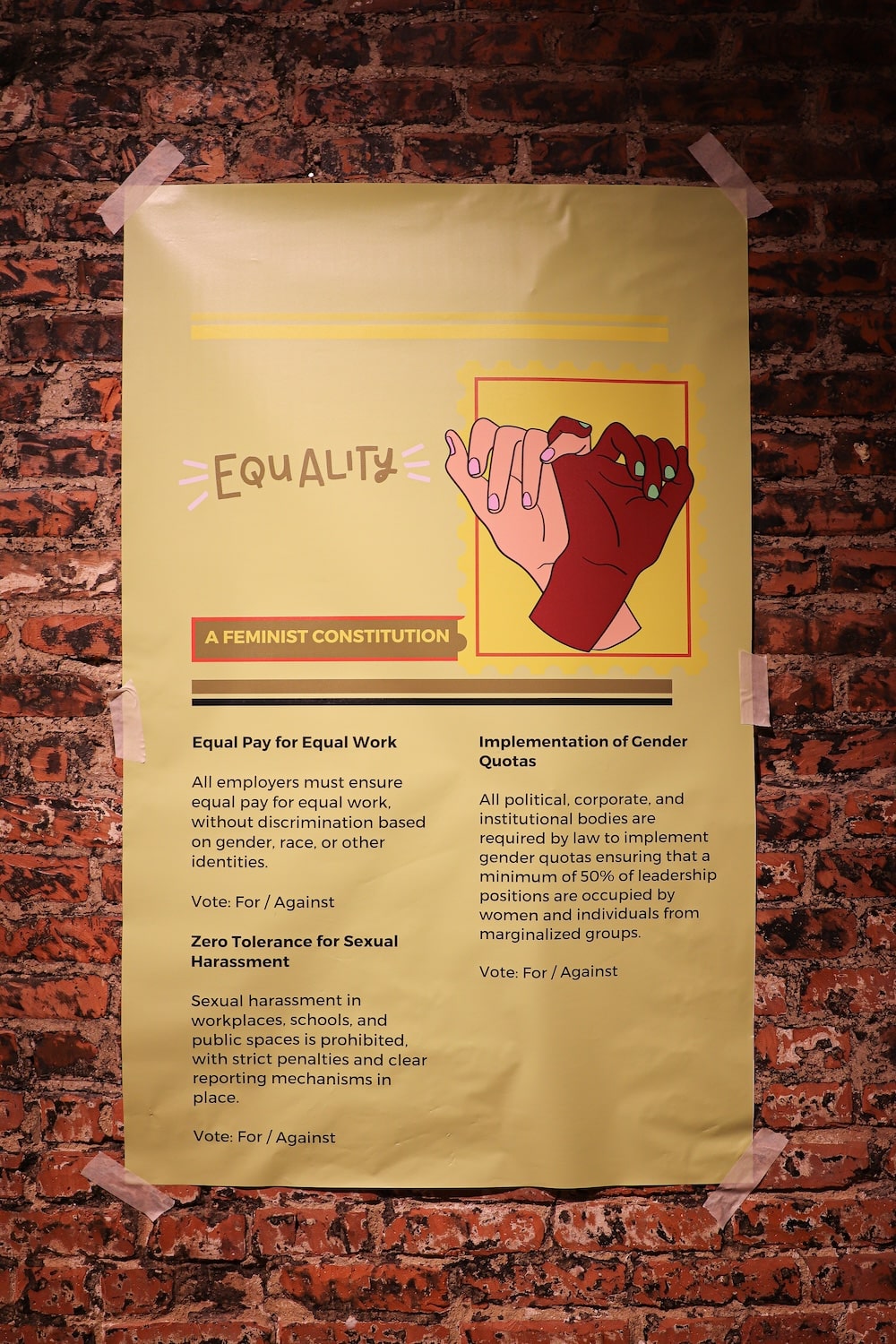

Practical implementation of taking a relational approach requires a participatory stance. By involving young people as partners, we enable them to shape systems – and to take an active part in changing the system – to support their wellbeing. This goes beyond metrics, embracing qualitative insights through meaningful engagement.

Case study: Vivo Mi Calle

Vivo Mi Calle was a project supported by Fondation Botnar’s Healthy Cities for Adolescents programme. A participatory initiative of Fundación Despacio, the programme sought to improve the health and wellbeing of children and adolescents in Cali, Colombia. It also empowered them by creating and regenerating public spaces and safe routes that promote their right to healthy cities.

To achieve its goal and effect real change, the programme considered the many elements at play, including the urban, environmental, technological, socioeconomic, and cultural contexts, involving young people in implementing the project. The programme was a success, reaching 18,000 young people.

Find out more about Vivo Mi Calle: Impact Generation with Vivo Mi Calle

Adaptive design means acknowledging that the context is complex and can change quickly, and this is key for successful programmes. Flexibility maintains relevance with evolving communities. We foster respectful, equal, and collaborative relationships with grantees and partners.

Evaluating interventions goes beyond data, embracing qualitative shifts in perceptions and experiences. Valuing young people’s lived experiences, the measurement of wellbeing includes their subjective outlook and fosters support networks among peers, families, and institutions. This process requires continuous learning by all partners.

How our partners think about wellbeing and relational approaches

Hear from our partner organisations and programme coordinators as they reflect on wellbeing and relational approaches in the initiatives we support.

At ThinkZone, wellbeing means valuing all opinions, positive or critical, related to our improvements. It involves actively fostering inclusivity, mutual respect, and open communication. Our team ensures everyone’s voice is heard, from members to the community and stakeholders. Wellbeing isn’t just discussion; daily practice creates a safe, collaborative space.

Promoting an open environment ensures effective programs and quick learning from mistakes. Prioritising opinions drives program adjustments and quality data collection for better evaluation.

ThinkZone values relationships among stakeholders (parents, educators, community, government, grassroots) for sustainable development. We prioritise continuous engagement, viewing work as an ongoing partnership fostering long-term connections beyond projects.

Read more about ThinkZone here.

The relational approach to wellbeing allows the Yoma team to focus on the young person in its entirety, in relation to the self, the others and the environment. While Yoma is a digitally enabled ecosystem, the relational wellbeing approach pushed us during the elaboration of the theory of change to ensure that we still address the young person with all their needs and multi-dimensional potential.

During the implementation stage, we combine the programme’s on- and offline dimensions. We have developed and are testing specific tools and questionnaires to measure the impact of Yoma on relational wellbeing.

Read more about Yoma here.

Currently, 90.4% of youth in Envigado, Colombia, and Bandung, Indonesia, feel empowered to make urban safety improvements. They envisage safer cities, engage power holders, and foster young people’s role in enhancing urban environments. With 23 initiatives launched or in development, and over 4,500 engaged youth, the S2Cities programme enriches urban environments, involving over 50 public sector officers.

The relational wellbeing framework is holistic, exploring wellbeing and underlying drivers of healthy environments. It urges youth input, stakeholder connections, and understanding processes. This insight spotlights safety’s roots in interactions with contexts, enabling targeted actions and broad collaboration.

This approach threads through the programme’s Theory of Change and local implementation, targeting personal, societal, and environmental wellbeing. Skill-building drives personal growth, while youth hubs foster trust. Inclusive public spaces and environmental initiatives emerge as pivotal. Monitoring rigorously evaluates outcomes, revealing shifts in youth safety and wellbeing drivers.

Read more about S2Cities here.

While not explicit, the concept of relational wellbeing is very much embedded in the Healthy Cities for Adolescents projects, which are focused on trying to improve adolescents’ experience of life in their cities, and this relies on understanding and strengthening their relationships and connections: with their peers, their caregivers, and with duty-bearers. It also often involves improving adolescents’ engagement with their environment – their experience of public spaces, for example, and the opportunities these spaces offer them to exercise, relax and socialise; or the routes they take to school and home and how safe these are.

Promoting this holistic view of wellbeing can look different in different countries and project contexts. However, what’s common to all our projects is putting adolescents at the centre of defining their needs and shaping their solutions. Through our projects, we also aim to better connect young people with the structures and platforms for them to voice their concerns and influence at a community, school, or city level. In much of our work, this ultimately means better connecting young people with city authorities and the mechanisms for influencing decisions about how cities and services within them are designed and run.

Read more about Healthy Cities for Adolescents here.

A commitment to wellbeing

In an increasingly interconnected and complex world, individuals or institutions cannot solely pursue wellbeing. An interconnected approach to wellbeing acknowledges the symbiotic relationship between individual needs, social connections, and perceptions of happiness. Fondation Botnar’s commitment to this approach represents a forward-looking perspective that values diverse human experiences, nurtures supportive communities, and fosters a deeper understanding of leading a healthy, fulfilling life.

By embracing this holistic approach, we can reshape our collective journey towards wellbeing and ensure that no one is left behind.

Thank you to our partners and the Relational Wellbeing Collaborative (RWB-C) for supporting our journey on relational approaches to wellbeing – read more about the RWB-C: https://rwb-collab.co/